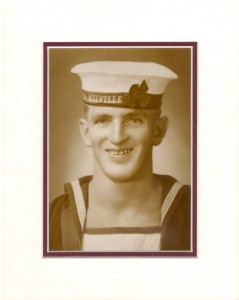

My father, Edward Walker Jeayes. photographer unknown, Sydney 28/6/1943

Against the wishes of his parents, my father, Edward Jeayes (aka “Snow” to his Navy mates) enlisted in the Navy during World War 2. Officially he was engaged on 24 November 1941 after he had passed Educational and Medical Examinations on 23 May 1941 and he was to serve for the duration of hostilities, which for him, meant just over four years. He had just turned 18 years old the month before he enlisted. Dad told me that he put a lock on the letterbox so that his parents wouldn’t get his call up notice and destroy it without him knowing.

Quite a few other sailors were engaged around the same time and they all became lifetime friends – Steve (C.A.) Constantine and Dale (A.D.) Arthur, Albert William Chappell (Bert aka Chappy) Tom (Thomas Walter) Gaunt and Ted (Edward Thomas) Cuneo. Bert Chappell was Dad’s best man at his wedding. Ted Cuneo told me that they did basic training together (Class 138) and I assume this is probably what initially bonded them all together. [1]In later years an Anzac Day reunion at the Sydney march was a regular event in their lives.

Dad began service at HMAS Cerberus the Navy Depot near Melbourne as an Ordinary Seaman. After completing his basic training he was then transferred to Darwin to HMAS Melville Navy Depot in April 1942, with his first shipboard posting being 6 months in 1942 on HMAS Maroubra (sometimes spelt Maraubra).

Travelling with Dad to Darwin was his best friend Steve (Charles Alexander) Constantine. When they arrived in Darwin, the first bombing had already taken place on 19 February 1942 and most non-essential civilians had been evacuated. The military forces were staying in the houses and digging trenches underneath them. Steve and Dad had travelled together on the train from Adelaide to Alice Springs and then by truck to Darwin. It was apparently rather a hellish trip, Dad thought Alice Springs was the end of the earth and biscuits were their main sustenance. Steve told me that they were all so sick of eating biscuits that he decided to take a risk and climbed out of the carriage and walked along to where he thought the food was. He climbed in and grabbed a box he saw that looked promising and took it back to their carriage where it was eagerly opened to reveal … yet more biscuits. [2]

The Maroubra was a 60 ton motor vessel used for Hydrographic Survey that had been requisitioned by R.A.N for service in the war effort. Dad and Steve Constantine did a lot of survey work together mapping reefs etc in and around Darwin for the Navy. When they were doing the survey work, they would go out reading with a tide pole. One of them would get out of the dinghy and wade in the water taking depths. They were told that they could name any features they found and mapped and it was expected they would name them after important Navy people etc. but they decided to name two of them after themselves. Hence JEAYES Reef Latitude: -12° 01′ S Decimal degrees -12.0172, Longitude: 134° 53′ E Decimal degrees 134.8985 and CONSTANTINE Reef or Reefs Latitude: -12° 07′ S Decimal degrees -12.1231, Longitude: 134° 55′ E Decimal degrees 134.9216.[3] They may have also named one after their Captain but I am not sure about that.

One time they were left on a mud island to be picked up at a certain time and weren’t. All they had were their rifles and Steve would shoot fish and eat them raw. Eventually someone did come and get them. Dad joked to Steve that if ever they were really shipwrecked the thing that would frighten him the most would be that Steve might eat him! Sometimes they stayed out on mud islands in the harbour in a tent and they could hear the crocodiles around them at might. Steve and Dad both were incredulous that they were never taken by the crocodiles. They also did work in the Daly River.[4]

Dad was promoted to Able Seaman on 24th November 1942. He also spent short periods aboard other survey craft including Kiara (a pleasure boat used for survey) and Vigilant, which was a Patrol Boat before the War.

Dad told me stories about his time in Darwin. He said he was to meet the son of his mother’s friend, Ida Turvey, on the wharf in Darwin one day when the Japanese raided. Ida had two sons that I know of, one Kenneth Leroy was in the Navy and the other, Frederick James was in the Army. Dad managed to get back to his ship and they headed for sea as they would not be such an easy target if they weren’t tied up to a wharf. This may have been the raid on 16 June 1942 which was one of the heaviest attacks on Darwin after the initial raid in February.

After 18 months in Darwin, Dad asked to do a Gunnery Course and was posted back to HMAS Cerberus at the end of 1943 to do his training. His mate Steve went too and he told me that my Dad topped the class. Many years later Dad and I visited HMAS Cerberus and he gave me a tour, showing me his classroom and also, much to my consternation, taking me to places marked off limits! We ran into an Admiral’s wife who questioned us but let us continue, much to my amazement.

While at Flinders, one of the popular places for Dad and his shipmates to go was to St Kilda where there used to be an amusement pier on the wharf. Young and Jackson’s in Melbourne was a favourite hotel where they often went to visit Chloe, a life sized nude painting that still hangs there today, although she has been moved upstairs.

He was then posted to a Corvette, HMAS Strahan (Pennant J363) on the day of his 21st birthday in 1944 as it happened and, at the same time, he was also made a Quarters Rating 3rd class (QR3). They departed from Sydney and sailed to the waters around New Guinea. War was a serious thing but there were some stories Dad told me that made me wonder how on earth we even won the War. The Commander during my Dad’s time was Lieutenant Commander Leonard Dale Williams who was posted to Strahan 27 March 1944 until May 1945 when command was taken over by Lieutenant Commander Ronald Ashman Nettlefold .

HMAS Strahan

So, one might ask, what does all this have to do with a hen?

Several papers ran the following story upon the return of HMAS Strahan which explains how that came about, including News (Adelaide, SA: 1923 – 1954), Thursday 19 April 1945, page 9:

‘Stray Hen’ Gave Crew Happy Memories of Service

When the “Stray Hen,” officially the Strahan, one of Australia’s latest corvettes, left Sydney Harbor just over a year ago, she left a wake like a corkscrew because half the crew had never been to sea and only three could steer.

It was different when the “Stray Hen” returned after more than a year of continuous service. She was brought into a home port with the precision of a battleship manned by a crack crew. She averaged 3,500 miles a month in covering 44,000 miles of the Pacific Ocean. She was commissioned on March 14 last year.

It was a happy company in the “Stray Hen”. Some of the crew were only 17 and 18, but they were all seamen by the time they returned.

NAME POSER

The Strahan was christened the “Stray Hen” by her crew after Allied servicemen in the islands had tried to pronounce her name. That was the nearest they could get to it. Until the Strahan headed back for civilisation she carried a large, lifelike representation of a “stray hen” [said to be a wandering Orpington] on her forrad gun turret, painted by one of the gun crew, Able-seaman Lobb, of Victoria.

Although the gun turret has now been covered by regulation grey, plaques painted for members of the ship’s company show the “stray hen” as a dashing seaman leaning on a bar counter with a cigar in one hand and a foaming pot of beer in the other.

Youngest member of the crew, Able-seaman E. W. Charlesworth, of George street, Clarence Park, was “captain for the day” when the corvette was at Wios Windee on Christmas Day. It is an old naval custom. The amusement created was one of the happiest memories of the year of service.

Borrowing an officer’s uniform for the occasion, A.B. Charlesworth was piped aboard in traditional style.

“Well, “Well, what’s buzzing, Lennie?” he asked Lieutenant-Commander Williams as he stepped on to the quarter-deck, using the crew’s nickname for their popular commander.

The assurance that there was nothing buzzing then brought the suggestion, rather timidly, from the “captain” that it was usual to offer some hospitality when a distinguished visitor came aboard. Captain-for-the-day Charlesworth soon found himself in the wardroom drinking the commander’s beer and smoking one of his cigars.

An inspection of the ship followed and “defaulters” were paraded.

One of the lieutenants found himself on a charge of impersonating an officer, and was ordered to scrub a companionway ladder. A laughing crowd of sailors stood by to see that the punishment was carried out, and the “captain” solemnly inspected the task.

“STARVING” CHARGE

“Starving the crew” was the unfounded charge brought against the Leading Supplier. His punishment was an order to fill a ship’s tank with 140 gallons of fresh water. It represented half an hour of hard work at the pump.

Barracoota fishing in Encounter Bay had its exciting moment as two officers and seven members of the crew, including Leading Seaman A. D. Mantell, of Glenelg, went overboard when the handrail gave way.

A depth charge had been dropped and a seaboat sent away to pick up fish. A number of fish came up near’ the stern of the Strahan. A sailor speared a 2-ft. long barracoota, and the officers and men were leaning against the rail watching his efforts to land it, when they fell.

While in the water, Seaman Mantell grabbed the fish. It sprang into life and Mantell let it go in astonishment. A cut hand was the proof of his fish story to shipmates.

My father told me about them using depth charges to catch fish but also that one day the Captain was ordering them to go slow when they were dropping them for submarines. Slower, slower, he kept saying until a member of the crew excused himself and advised the Captain that if they went any slower, Sir, they would blow themselves up.

After they gained control of the ship that first day, they sailed first to Langmack [Langemac] Bay then onto Lae, Finschhafen, Madang, Wewak, Hollandia and they also visited New Britain. Their duties at that time were mainly escorting convoys of cargo and ammunition ships into the islands after American or Australian troops defeated the Japanese in possession. Sometimes the allies did not try to take an island from the Japanese but would miss one and just take the ones around it thereby effectively starving the Japanese out as their supplies were cut off. They also were required to do sub-marine detection on reefs and general patrols.

In October 1944, Strahan was present in Morotai Harbour when the recently-captured island was attacked by Japanese aircraft. The corvette was attacked by a dive-bomber, but was able to drive off the Japanese plane before she was damaged. It is scary to think Dad would have been on the guns. Two or three air raids a night were common. Apparently the incident doesn’t appear in the Official History but CPO Blair Mason, who was aboard at the time, told the Corvette Magazine:

“It was hard to say whether he was a suicide bomber or not, but it was a single plane and it was engaged by our 4-inch gun,” he said. It was quite obvious that one of our shells damaged the plane because it lost height and started spiraling towards the ground. An American Bofors on the shore engaged it on its way down and blew it apart. The next day, when an American barge came alongside, one of the Americans said, ‘you guys were robbed, you definitely got that plane, but our guys have claimed it‘.”[5]

“Natives at Morotai” from my father’s collection. Photographer unknown, possibly Ken Lamb, 1945

Their tour lasted 12 months with one sighting of “civilisation” when they returned to Townsville while the bottom of the ship was scraped of barnacles etc. Queen Wilhemina of Holland was very grateful to the Australian Defence Forces and wished to pay each member for having helped drive the Japanese out of Dutch New Guinea but the Australian Government would not allow it.

It was during this time in the tropics that Dad took to sleeping on deck in his hammock whenever possible. He couldn’t do it in big seas as he would have been washed overboard from the corvettes but it was much cooler than in the sleeping berths. While I don’t think they lost anyone overboard, the ship’s tomcat, Bollocks, did go overboard once in between Strahan and another ship and one of the crew had to be lowered down to rescue him.

Corvettes were known as the “little ships”, they were one of the smallest warships in World War 2 where everyone learned “to live for years like sardines in ships that could be blown out of the water by pretty well any enemy ship they met”. [6]

The men who handle the Little Ships have got no band to play,

And spend their lives in endless watch, ceaselessly night and day.

The little craft turn somersaults, where the liner only dips

And crashing seas make music for the men in the Little Ships[7]

That verse and the following describe exactly the impression my father gave me.

The little ship punched her bow into the huge green-black wave, the sea, a lighter green now and frothing, raced along the ships fo’c’sle shooting spouts of water up from the guard-rails, the bollards and the 4” gun, then smashed into the bridge superstructure and tumbled down into the ship ‘s waist, and ran along the quarterdeck. The ship shuddered and shook and pushed her cheeky nose up and the water cascaded over the side and into the sea. Then the ship’s stern heaved up as the wave swept aft, and the nose pointed into the trough. The little ship punched her bow into the next huge green-black wave and the next …[8]

Apparently “even in dry dock they would roll if a heavy dew fell” and “merchantman would sometimes report that they could see down the funnels of the corvettes as they heeled and heaved in the seas.”[9]

I recently travelled on “a liner” to Papua New Guinea, on occasion when the ship rocked and rolled in the big swells, I thought of Dad and the other sailors in their little ship, punching the bow into the next huge green-black wave. I also thought about the endless days and nights at sea without any of the luxuries and entertainments that I had on hand but I remembered my father’s fond memories of the mateship he had illustrated by the two photos below taken aboard H.M.A.S. Strahan.

Vic Hutchinson, Eric Anderson, my father and Alby Irwin. Photographer possibly Ken Lamb. c 1944

“Chappy” Chappell and my father. Photographer believed to be Ken Lamb. c 1944

My father told a story that most of the crew had no idea what they were doing when they were first assigned to the ship and I think that is borne out by the newspaper article earlier in the story. He also said that the Captain of the ship was a schoolteacher, selected from amongst the men because he would be able to transfer his skills of leading children over to that of leading men. As the real Captain was a career RAN Officer, I suspect that the appointment might have been Officer of the Watch, the direct representative of the Captain, and that it may have been Dad’s best friend “Chappy” pictured above and a schoolteacher before signing up, that was Officer of the Watch and the basis of Dad’s story.

In May 1945, HMAS Strahan travelled to Adelaide via Sydney, where she underwent a refit. Following this, she was immediately deployed back in New Guinea, and in June 1945 fired upon Japanese gun emplacements on Kairiru Island. The corvette received two battle honours for her wartime service: “Pacific 1944-45” and “New Guinea 1944”.[9]

My father didn’t stay with H.M.A.S. Strahan after she returned from service in May 1945. Instead Dad was based around HMAS Penguin at Balmoral in Sydney. According to Dad, he and a mate had gone AWL in Adelaide as they had not had any shore leave in a long time. They knew that the ship was going to Sydney so he and his mate hitch hiked to Sydney and re-joined the ship. This was apparently around 6 June. At the interview (Court Martial?) into why he had jumped ship and what he wanted to do he confessed his wish to be on a bigger ship. He spent some time at Holsworthy, the Military Prison and according to his Service Record, he was sentenced to 90 days on 15 June. Apparently he did not serve his full sentence though as he was released on 21 August 1945 and married my mother on 28 August 1945.

My parents wedding 28 August 1945. My father wears a white ribbon rather than the normal black ribbon. Photographer Laurance Lupton, Hurstville NSW

Good behaviour may have played a part in his early release and also his impending marriage to my mother. Dad never mentioned Holsworthy, I guess he wasn’t too proud of that bit, his words were he “spent some time working in and around HMAS Penguin” so I guess that covered it. However and surprisingly to me, his wish was granted and after spending a month or so at the Naval Base HMAS Penguin he was posted to HMAS Hobart (Pennant No. D63). It was 21st September 1945 and HMAS Hobart had just returned from Japan after being present for the surrender ceremony on board the Missouri on 2 September.

They left for Japan 5 November and arrived in Tokyo on 17 November 1945. Even though Japan had surrendered after the atom bomb drops by America in August, the journey continued as planned long before and the crew of the HMAS Hobart were in Japan for quite some time, but they were not part of the Occupying Forces. For this reason they were able to get in quite a bit of sightseeing as they were officially on leave.

Dad visited Yokohama seeing Mt Fuji capped with snow, the Sacred Bridge and the Emperor’s Palace. Dad didn’t have a lot of spending money as most of his pay was allotted home so he found ways to earn extra. He ironed the Petty Officers shirts for 6p a shirt on the trip to Japan and sold various items to the Japanese including an old tin of sugar for 800 yen which is about $9 today! He was able to visit the Club Ashore and a bottle of beer cost 2.5 yen and he also bought many fine silks and linen. They caught the tube railway to Nikko, which is in the mountains, and it was snowing heavily. There they stayed at the Konishi Inn.

My father (3rd from the left) and some of his Hobart shipmates, Konishi Inn. Photographer Unknown. c.1945

My father and a Hobart shipmate at the five storey pagoda Nikkō Tōshō-gū, Nikko, Japan. Photographer unknown c 1945

The Hobart sailed from Tokyo and up into the Inland Sea to Hiroshima where Dad saw the destruction caused by the Atom Bomb that was dropped there. There was only one structure standing – the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotional Hall now called the Genbaku Dome but the interior had been blown away. Near where what were once some houses he found a stack of bottles and they had melted together. He took one of the bottles as a souvenir which my brother has in his possession. I saw this building myself in the area now called the Peace Park in Hiroshima some years ago and I recognised it straight away as it was exactly as Dad described. It was surrounded by long grass and fenced off. As I stood in wonder a stray cat wandered out and it all seemed so surreal.

Genbaku Dome, Hiroshima Japan, 2007. Photographer Lyn Nunn

While serving in the Navy, Dad also collected what is known as trench art. In spite of its name, trench art was rarely actually made in the trenches. However, pieces of scrap material, faulty ammunition and other “trophies of war” like the propellers of captured aeroplanes were often fashioned into souvenirs during quiet times, convalescence or after a return home from combat. Although it has always been a pastime of soldiers and sailors, decorated objects made of war materials from 1914 onward are those usually known as trench art.[11] Several pieces are now in my possession. The first is a silver tin locket with a red “ruby” which is actually a piece of red toothbrush handle. It was made aboard the Strahan by Johnno (Johnson), the gunner. The other pieces are butter knives made on board the Hobart on the way to Tokyo by the gunnery men. It was a good way for the gunners to make money for extras. These knives have been fashioned from bullets which are the handles. Each blade is inscribed HMAS Hobart Tokyo. I have two serviette rings made aboard Hobart. There is also a tie pin with the same kind of decoration as the locket which I suspect is also trench art. All are pictured below.

Various items of trench art and a stocking tin that may also be trench art brought back by EW Jeayes WW2.

Photographer Lyn Nunn 2016

Whilst in Japan, Dad’s service time was up and he returned to Australia aboard an English U Class Destroyer, HMS Undine, (Pennant No. R.42) which was commanded by a New Zealander. His final discharge was from the depot HMAS Rushcutter on 6 February 1946. HMAS Hobart did not return to Sydney again until 2 April 1946.

Notes on my sources that may help others:

My father and I had many conversations over the years about his life and particularly in the last few months of his life when he lived with me. Many of the facts in this story are from notes I took at the time or soon after for future reference.

Apart from those conversations and conversations with his shipmates, I have also used his and other crew service records and second hand ship histories to establish and verify names, dates and places.

The H.M.A.S. Strahan Association published 72 Newsletters between 1987 until 2007. My father and then I subscribed and I have many copies of them in my library – they have been a great source of information. Although I haven’t seen any there was a ship publication Strahan Strand – something to look for from other ships.

Some Online resources – others may be mentioned in the end notes:

http://cecopaint.wixsite.com/ranca-nsw – I also have some of their newsletters,

http://www.navy.gov.au/hmas-strahan

http://hmashobartassqld.org/index.html

http://www.naa.gov.au/collection/explore/defence/service-records/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMAS_Strahan

[1] Cuneo, Ted, sympathy card in author’s possession, December 2003

[2] Phone conversation with Steve Constantine of Berry, NSW, 14 February 2009

[3] Northern Territory Government, NT Place Names Register, http://www.ntlis.nt.gov.au/placenames/ accessed 10/8/2017

[4] Phone conversation with Steve Constantine of Berry, NSW, 14 February 2009

[5] Extract from Corvette Magazine, ‘Strahan’s Stolen Success’, http://cecopaint.wixsite.com/ranca-nsw/hmas-strahan accessed 10/8/2017

[6] Walker, Frank R., Corvettes – Little Ships for Big Men, Kingfisher Press, Budgewoi NSW, 1995, pg. 7

[7] Petty Officer D.C.R., H.M.A.S. 1942, Royal Australian Navy Corvette Association, “Little Ships” extract from Corvette Magazine, undated http://cecopaint.wixsite.com/ranca-nsw/corvettes-other-stories

[8] Walker, op.cit., pg. 13

[9] Ibid., pg. 25

[10] Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMAS_Strahan accessed 6/9/2017

[11] Alan Carter, ‘Trench Art’, Treasure Hunt, (http://abc.net.au/treasurehunt/s934995.htm) accessed 17 September 2003.

©Lynette Nunn 2017